Amy Chua, professor of law at Yale University, recently published a controversial essay in the Wall Street Journal entitled “Why Chinese Mothers are Superior.” This essay is essentially an excerpt of larger book entitled Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother recently published by Penguin Press. The object of her essay is to provide an explanation for why Chinese students are “stereotypically successful.” Chua argues that the Chinese mother child relationship is one defined by an overwhelmingly strict regime of rules and expectations coupled with ample forms of humiliating criticism when those rules are broken or when expectations are not met.

Pretty much everything that kids today take for granted, from watching TV to playing computer games and even (interestingly enough) acting in a school play, is verboten under this regime. Instead, classical music, math and science are, unsurprisingly, privileged. Chua ultimately argues that this form of parenting works best to induce a measure of self-respect through excellence. Indeed, throughout the article, Chua makes no effort to disguise her own disdain for “Western” concerns with the child’s psyche and self-esteem which leads to indolence and weakness. Her argument has naturally provoked a wide variety of responses, from horror at what is perceived as abusive child-rearing to outright approval. Others have righty criticized Chua’s untenable binaries between Western and Chinese mothers and their values, or whether all or even most of Chinese mothers raise their children as she does.

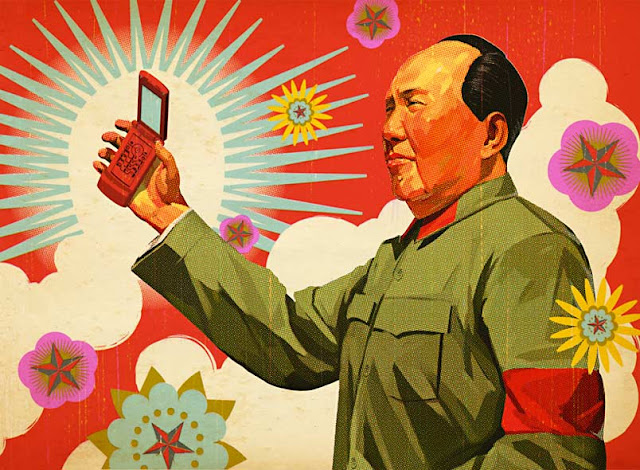

Whether or not the so-called ‘Chinese/Chua mother’ approach is the necessary one to raise successful children is obviously open to question; and I have my own serious doubts about its assumptions and arguments. But what makes this article particularly interesting is that it comes at a time when there is a rising fear of decline in the US imperial position in the world, especially with respect to China. Chua’s article on pedagogy resonates between familial insecurity about the future, the shattering of the American dream for the vast majority of Americans in the aftermath of the great recession and ultimately about the endurance of American’s political and economic global hegemony. Only, as far I have read, has Judith Warner in a New York Times review inchoately made this point in addressing Chua’s book.

To be sure, the relationship between imperial governance and pedagogy is by no means farfetched. One can go back to Tacitus’ Germania for a critique of decadent and effeminate Roman values and moral education compared with the ‘vigorous’ Germanic youths: of course, this at a time when the Roman Imperium was in its ascendancy in the year 96. But, more recently at least, pedagogy and parenting was of the utmost concern among imperial administrators in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Ann Stoler, for example, has done most to show that “The management of sexuality, parenting, and morality was at the heart of the late imperial project” such that “In the nineteenth century Indies cultivation of a European was affirmed in proliferating discourses on pedagogy, parenting, and servants - microsites in which bourgeois identity was rooted in notions of European civility, in which designations of racial membership were subject to gendered appraisals, and in which ‘character,’ ‘good breeding,’ dispassionate reason, and proper rearing were part of the changing cultural and epistemic index of race” (Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power, 110, 144). Fear of miscegenation and the influence of local servants on children raised in the colonies were fundamental topics of concerns for colonial administrators who believed that only through a restrictive moral, educational and psychological pedagogy can European self-identity and its imperial project be maintained.

Of course the issue today differs from an overt 19th century imperial concern with race to one of renewed concern with the geopolitical and economic competitiveness of American Empire. It is not by chance that Chua’s article comes on the heels of proliferating news stories about China’s greater than expected military capabilities. A few months ago, for example, James Krask published an essay entitled “How the United States Lost the Naval War in 2015” in which he posits a scenario where the US navy no longer has supremacy of the East China Sea. Recent information on a new Chinese stealth fighter highlights China’s technological military prowess that potentially rivals the US air supremacy.

On top of military hardware advances is the widespread perception of China’s economic and productive might, its accumulation of enormous dollar reserves and its ability to use its economic position to push its own agenda in various international fora. Whereas China has become the manufacturing giant of the global economy, the US is left with a bloated financial sector whose benefit is largely overstated.

More to the point, much of this concern with American decline is then refracted through a growing idea over the past few years that American public education is in crisis, especially in its failure to adequately train students in science and math. For example, the Programme for International Student Assessment ranks countries on the basis of math and science testing. Its 2009 result reveals that the top five countries for math and science are lead by China, followed by Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan and Finland, Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, respectively. The United States ranks 30th in math and 23rd in science. Thus in recent years there has been a growing call to privatize US education in the form of either vouchers for private schools or charter schools as a means of reinvigorating education by dismantling public sector teacher unions.

But Chua’s article it seems to me goes one step further in its explicit argument that culture remains a central aspect for addressing questions of education. Her essay is indeed firmly positioned in the culture war discourse (thus seamlessly appearing in the Wall Street Journal) by emphasizing a rigidly hierarchical family nucleus as the means for reasserting individual control at a time when American families feel a growing social and economic insecurity at home. This return to a concern with parenting, nonetheless, diverts us from the need to attend to the deleterious effects a neoliberal political economy has produced for over thirty years, with its generation of crises, neglect of the infrastructure of consumption, reckless disregard for the environment, production of extreme inequality, disregard for public education and commitment to authoritarianism within organizational life.

Blog Archive

-

▼

2011

(37)

-

▼

January

(7)

- Speed, Democracy, Revolution: Tunisia, Egypt, and ...

- The Geopolitics of Motherhood

- Corruption and Class Struggle: What It’s Like to L...

- The Radical Right, The Extreme Right and The Repub...

- In the Crosshairs

- Impossible demands for "proof" in the Giffords ass...

- Where the Real Threat Lies: Julian Assange and the...

-

▼

January

(7)

Popular Posts

-

Ed began making barrels in 1975. He no longer builds rifles. Hudson Valley Fowlers by Kenneth Gahagan Alan Sandy Rifle Damascus Barrel for G...

-

James Julia Auction October 14th, 15th, & 16th Extraordinarily rare and important signed John Armstrong Kentucky pistol, believed to be ...

-

Pennsylvania painted pine dower chest, ca. 1800 , retaining a vibrant salmon swirl decorated surface, 24 1/4" h., 41 1/4" w. Copy ...

-

I made this knife from a file back in 1975. It was all hand work with files and stones; both my eye and grip were better then. A friend, now...

-

The trunk was made by Steven Freede, The Trunk Shop, in Colorado, about 20 years ago. Photo supplied by Sharon Brimer.

-

Photographed at the 2013 Lake Cumberland Show by Jan Riser.

-

Ball-headed club Iroquois (Mohawk) Wood, ribbon, feather Length 52 x width 13.5 x cm 18th century Area of Origin: Great Lakes, Canada Belong...

-

This heart design is based on the patten from an antique bag that Jimmy restored. leather insert to accommodate the straps what detail Jimmy...

-

I have the privilege to know Bob Roller and would like to show five of his locks. From top to bottom and left to right Twigg Durs Egg, Durs ...